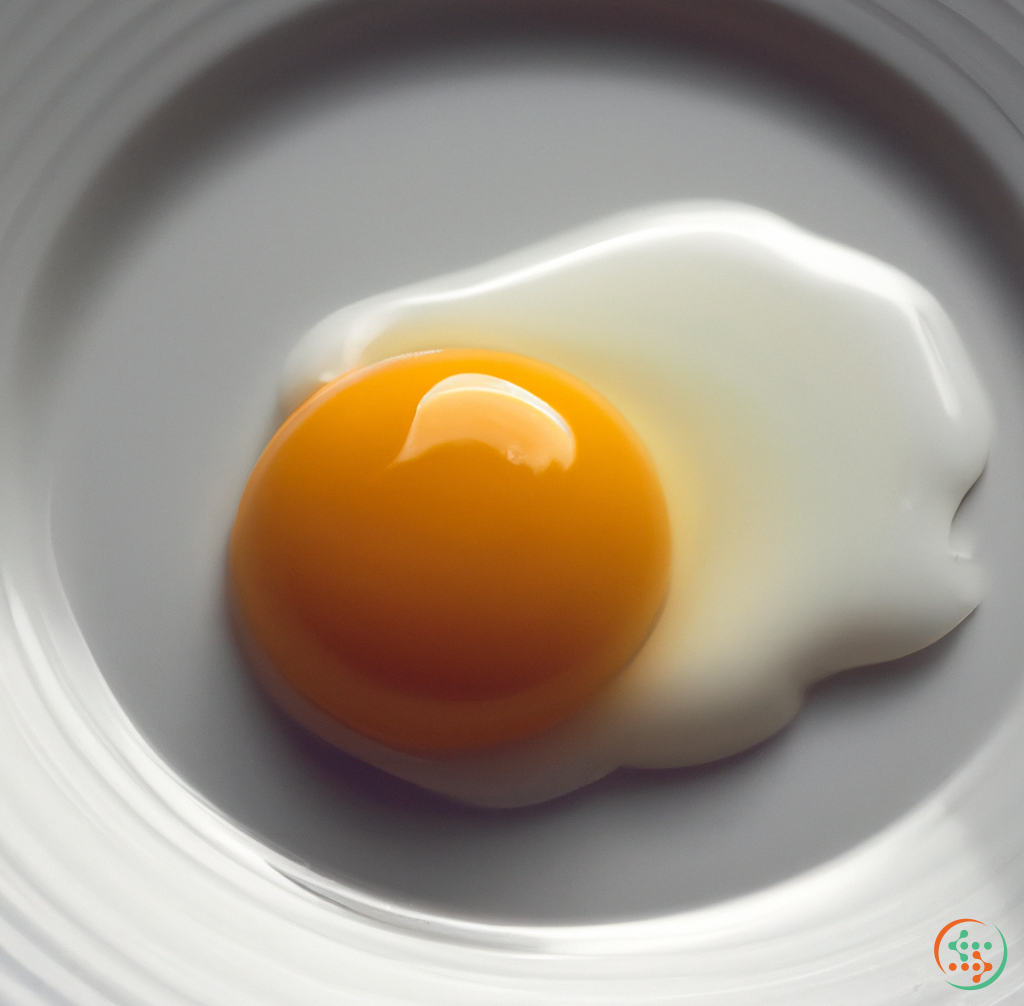

Raw Egg Yolk

, why it’s good for you and how it can be used

Raw Egg Yolk – Health Benefits, Uses, and Tips for Cooking

Egg yolks are an incredibly versatile food, and they’re incredibly good for you too. Not only are they great in savoury recipes, but they’re also packed full of essential nutrients and minerals our bodies need. However, an increasingly popular way to enjoy eggs is to consume raw egg yolk, and although it might sound strange, this can be an excellent way to squeeze even more nutrition out of each egg. But just what is a raw egg yolk and what are the health benefits? How can raw egg yolks be safely consumed, and what are the best ways to cook them? Let’s take a look.

What are raw egg yolks?

Simply put, raw egg yolk is the yellow (or in some cases, orange) centre of an uncooked egg. It is produced by female birds, including chickens and quail, after the ovaries of a hen release a yolk into the oviduct. This then combines with albumin, creating the whole egg. When the egg is uncooked, the albumin has not set and can be easily separated from the yolk.

Benefits of Raw Egg Yolks

Egg yolks are an incredible source of health benefits, and when eaten raw, they can provide even more nutrition than when cooked. Here is just some of the rich content found in one raw large egg yolk:

Vitamin A- 15% of the RDI

Vitamin B-12- 6% of the RDI

Folate- 4% of the RDI

Vitamin B5- 4% of the RDI

Phosphorus- 9% of the RDI

Calcium- 10% of the RDI

Selenium- 18% of the RDI

Fat- 34% of the RDI

Cholesterol- 212 mg

Protein- 3.6 g

The primary benefit of consuming raw egg yolks is that they provide a convenient and inexpensive way to increase your nutrient intake. Even if you’re getting enough protein from other sources, eating raw egg yolk is an easy way to ensure your body is getting the right amount of vitamins and minerals taken in daily.

Raw egg yolks are also packed full of antioxidants like lutein and zeaxanthin, which are important for protecting the body from damage caused by free radicals. They also help maintain vision and skin health, as well as having anti-inflammatory properties.

Cooking Raw Egg Yolks

Eating raw egg yolks is not for everyone, since there’s the risk of salmonella poisoning. But if you do decide to do it, there are a few rules to follow to make sure it’s as safe as possible.

Firstly, use eggs that are as fresh as possible, ideally still in date. Look for eggs with a clean, uncracked shell and no visible damage. It’s always best to cook eggs until the whites and yolks are firm, but if you do decide to consume them raw, you should use pasteurised egg products, as these have been heated to destroy any potentially harmful bacteria.

Egg yolks can be eaten raw on their own or blended into smoothies, sauces, or mayonnaise. They can also be lightly cooked in a hot pan while still runny, like poached or soft-boiled eggs. Keep in mind that overcooking raw egg yolks can reduce their nutritional value significantly, so it is important to monitor them carefully when cooking.

Tips and Tricks

Here are a few tips and tricks for those looking to get more out of their egg yolks:

- Use regular, large eggs for the most nutritional bang for your buck. They’re inexpensive and provide the greatest nutrient density.

- Separate the whites from the yolks carefully – use an egg separator to avoid any cross-contamination.

- If you don’t want to eat your raw egg yolks straight away, freeze them in ice cube trays for easy portioning. Thaw and use as you need them.

- To cook raw egg yolks, poach them for 2-3 minutes or until the yolk is starting to set at the edge.

- Add raw egg yolks to emulsions like mayonnaise, vinaigrettes, or salad dressing to give them a creamy consistency and additional nutrition.

Conclusion

Raw egg yolks are an incredibly nutrient-dense food that can offer a range of health benefits, from supporting vision and skin health to providing an abundance of minerals and vitamins. Plus, they’re surprisingly versatile and can be used in a variety of recipes, like sauces and dressings. If you’re looking for ways to increase your daily nutrient intake, then why not give raw egg yolks a go? Just remember to adhere to food safety guidelines to avoid any nasty surprises.

Raw Egg Yolk: Exploring the Science Behind Its Journey from Farm to Plate

We’ve all taken a bite of an egg yolk before. Whether we’re downing breakfast scrambles, indulging in creamy deviled egg recipes, or using raw egg yolks for baking, the yellow center of a chicken egg is instantly recognizable. But what actually goes into making a raw egg yolk and ensuring that it reaches our dinner plate? From the moment it’s created to when we add it as the finishing touch to a delicious meal, tracing a raw egg yolk’s journey is a fascinating exploration of science and biology.

In order to understand the process of raw egg yolk creation, we must first discuss the anatomy of a chicken egg. Chicken eggs are composed of an inner egg white (or albumen) layer and an outer eggshell, both of which are surrounded by a membrane located between the egg white and the shell called the albumen sac. The majority of an egg’s contents are located in the egg yolk, or the yellow center. According to the USDA, the average large egg yolk contains approximately 18% of the egg – 60% of the egg’s calories, 42% of the egg’s protein, and 31% of the egg’s fat.

So, where does a raw egg yolk come from? As you may already know, chickens are birds, which means they lay eggs. But why do chickens lay eggs in the first place? To answer that question, we must explore the biology behind a chicken egg’s creation and journey.

A chicken egg begins its life in the hen’s ovary, which is composed of several small follicles. Two types of cells exist within these follicles: theca cells, which secrete hormones and provide a supportive framework for the egg; and the granulosa cells, which are responsible for developing the egg itself.

The egg begins its development in the immature follicles and is fed by the blood vessels that supply the ovary. During the fertilization process, sperm is released into the vagina and travels to the uterus. Once the sperm is ejaculated, the ovary begins releasing a hormone called follicle stimulating hormone which triggers the release of the egg from its follicle. As it continues its journey, the egg makes its way up the oviduct and into the oviduct portion of the uterus.

Once the egg enters the uterus, it begins to build layers. The innermost layer of the egg is the yolk membrane, which is composed of a protective, thick protein membrane which helps keep the yolk intact. In the next layer, the perivitelline fluid forms an elastic gel surrounding the yolk to provide a cushion and prevent the yolk from breaking. The supracloacal albumen, or egg white, is comprised of two parts: the chalaziferous layer and the inner albumen, which contains most of the egg’s liquid content.

The shell of the chicken egg is made up of three separate layers. The innermost layer, or the shell membrane, is composed of a type of lipoprotein and phospholipid blend of proteins which create a waterproof barrier for the inner contents of the egg. The middle layer is made up of calcium carbonate which provides strength and rigidity to the shell, while the outer layer is comprised of a lipoprotein mixture which serves to protect the egg from moisture.

Once the raw egg yolk has been created, it must now make its way to the dinner plate. In order to do this, it first needs to be transported from the hen’s reproductive system to a farm. After the egg is laid, it is collected and immediately taken to the farm where it is thoroughly cleaned and stored in a cool and dark place. From there, the egg can be transported to packing areas, processing plants, and eventually grocery stores.

Once the egg has reached the grocery store, consumers have the opportunity to purchase the egg. It is important to note that the egg should not be stored at room temperature for an extended period of time, as bacteria and other contaminants can grow in the warm environment. Instead, eggsshould always be stored in the refrigerator and only taken out shortly before they are to be cooked or eaten.

Once the egg reaches your kitchen, it’s ready to be prepared. When cracking the egg open, it’s important to take care not to damage the yolk, as broken yolks can leak nutrients and make the egg less nutritious. Additionally, cracked eggs should never be consumed raw due to the potential presence of salmonella or other foodborne illnesses. Therefore, it is always recommended to cook eggs completely before consuming.

Whether you’re making sunnyside-up eggs, a rich hollandaise sauce, or mixing egg yolks in for added richness in a cake batter, raw egg yolks bring flavor, nutrition and texture to many dishes. By understanding the biology and science behind raw egg yolk creation and its journey from farm to plate, we are able to appreciate the incredible journey these little yellow centers undergo in order to reach our dinner table.

| Vitamin A | 0.381 mg | |

| Beta-Carotene | 0.088 mg | |

| Alpha-Carotene | 0.038 mg | |

| Vitamin D | 0.0054 mg | |

| Vitamin D3 | 0.0054 mg | |

| Vitamin E | 0.00258 grams | |

| Vitamin K | 0.7 ug | |

| Vitamin B1 | 0.18 mg | |

| Vitamin B2 | 0.53 mg | |

| Vitamin B3 | 0.02 mg | |

| Vitamin B4 | 0.8202 grams | |

| Vitamin B5 | 0.00299 grams | |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.35 mg | |

| Vitamin B9 | 0.146 mg | |

| Vitamin B12 | 0.00195 mg |

| Calcium | 0.129 grams |

Daily Value 1.3 g

|

| Iron | 0.00273 grams |

Daily Value 0.018 g

|

| Magnesium | 0.005 grams |

Daily Value 0.4 g

|

| Phosphorus | 0.39 grams |

Daily Value 1.25 g

|

| Potassium | 0.109 grams |

Daily Value 4.7 g

|

| Sodium | 0.048 grams |

Daily Value 2.3 g

|

| Zinc | 0.0023 grams |

Daily Value 0.011 g

|

| Copper | 0.08 mg |

Daily Value 0.9 mg

|

| Manganese | 0.06 mg |

Daily Value 0.0023 g

|

| Selenium | 0.056 mg |

Daily Value 0.055 mg

|

| Tryptophan | 0.177 grams | |

| Threonine | 0.687 grams | |

| Isoleucine | 0.866 grams | |

| Leucine | 1.399 grams | |

| Lysine | 1.217 grams | |

| Methionine | 0.378 grams | |

| Cystine | 0.264 grams | |

| Phenylalanine | 0.681 grams | |

| Tyrosine | 0.678 grams | |

| Valine | 0.949 grams | |

| Arginine | 1.099 grams | |

| Histidine | 0.416 grams | |

| Alanine | 0.836 grams | |

| Aspartic Acid | 1.55 grams | |

| Glutamic Acid | 1.97 grams | |

| Glycine | 0.488 grams | |

| Proline | 0.646 grams | |

| Serine | 1.326 grams |

| Galactose | 0.07 grams |

|

| Glucose | 0.18 grams |

|

| Fructose | 0.07 grams |

|

| Sucrose | 0.07 grams |

|

| Lactose | 0.07 grams |

|

| Maltose | 0.07 grams |

|

| Total Sugars | 0.6 grams |

per 100g

|

| Caprylic acid (8:0) | 0.01 grams |

|

| Capric acid (10:0) | 0.01 grams |

|

| Lauric acid (12:0) | 0.01 grams |

|

| Myristic acid (14:0) | 0.1 grams |

|

| Palmitic acid (16:0) | 6.86 grams |

|

| Stearic acid (18:0) | 2.42 grams |

|

| Arachidic acid (20:0) | 0.03 grams |

|

| Behenic acid (22:0) | 0.04 grams |

|

| Lignoceric acid (24:0) | 0.01 grams |

|

| Total Saturated fatty acids: | 9.49 g | |

| Erucic acid (22:1) | 0.01 grams |

|

| Oleic acid (18:1) | 10.7 grams |

|

| Palmitoleic acid (16:1) | 0.92 grams |

|

| Gadoleic acid (20:1) | 0.09 grams |

|

| Total Monounsaturated fatty acids: | 11.72 g | |

| Omega-3 Timnodonic acid (20:5) | 0.01 grams |

|

| Linolenic acid (18:3) | 0.1 grams |

|

| Linoleic acid (18:2) | 3.54 grams |

|

| Total Polyunsaturated fatty acids: | 3.65 g | |

| Cholesterol | 1.09 grams |

|

| Total Sterols: | 1.09 g | |